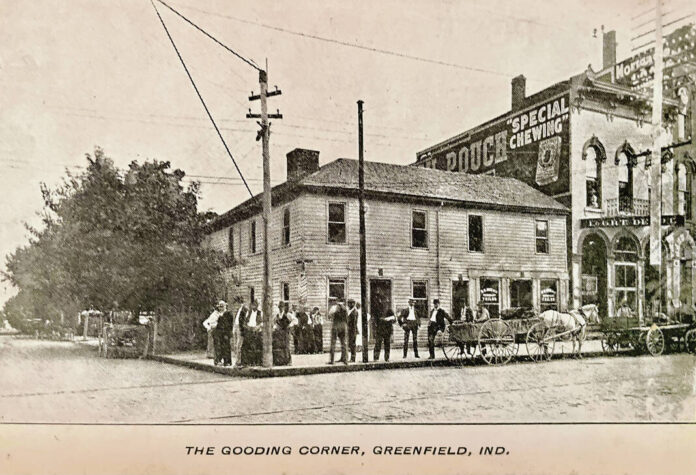

A mid-19th century rendering of downtown Greenfield shows the former Gooding Tavern on the southwest corner of State and Main streets. Prominent Black businessman George Knox opened his barbershop in the 1860s inside the tavern, where Greenfield City Hall now sits.

GREENFIELD — The story of George Knox — Greenfield’s first black businessman — is currently on exhibit at the James Whitcomb Riley Museum in Greenfield, and local historians don’t want you to miss it.

The exhibit is on display through Sept. 6 and is free to the public.

“George Knox has quite a story to tell. He was one of the most prominent Black citizens of his era,” said Gwen Betor, a longtime docent at the Riley museum.

Before rising to a life of prominence, Knox was born into slavery in 1841. When his parents’ master died, his family members were sold again.

His father held a 3-year-old Knox in his arms as he stood on the auction block in Tennessee. Knox and his brother and sister were sold to the same owner, which meant the siblings could keep in touch. But they were separated from their parents, who would die three years later.

Historical accounts of Knox’s life have shared that his master brought him along when he fought for the Confederates in the Civil War. When the slave owner was later redrafted and wanted Knox to join him again, Knox reportedly ran away and joined the Union Army.

According to historical accounts, Knox served alongside a number of soldiers from the Greenfield and Knightstown areas.

That’s why, after failing to get his first barbershop venture to take off in Indianapolis, he opted to give it a try in Greenfield.

Knox reportedly borrowed $2 to move his shop 30 miles east to Greenfield, where he opened up shop in the former Gooding Tavern where Greenfield City Hall now sits. It was there that he gained a following for his barbering skills, as well as his gift of gab.

According to one historical account, “his customers enjoyed a haircut but also the sharing of stories. Mr. Knox would say that he had an MD after his name, which of course many thought this was a medical term. In actuality, he was a mule driver during the Civil War.”

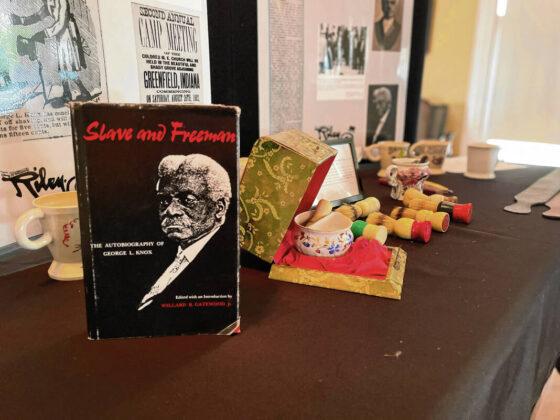

His tattered red barber’s chair is on prominent display at the Riley Museum, along with shaving mugs, brushes and signage from his shop.

Historians say he enlisted the help of a young James Whitcomb Riley to hand paint personalized ceramic shaving mugs for individual customers, to reduce the risk of spreading skin disease.

Hancock County historian Joe Skvarenina said Knox played a pivotal role in Riley’s life before the latter found fame as the national poet laureate.

“He gave Riley some work when Riley didn’t have any work,” said Skvarenina, who featured Knox in his book, “Also Great: Stories of the famous and not-so-famous of Hancock County.”

In the mid-1880s Knox moved back to Indianapolis where he created a chain of barbershops, eventually managing about 50 barbers. Riley, who also relocated to Indianapolis, continued to be among the many prominent men who would visit his shops.

Knox is said to have counted former president Benjamin Harrison among his customers. He was also acquainted with prominent figures like Booker T. Washington, Frederick Douglas and Madam C.J. Walker.

In addition to barbering, Knox also excelled at publishing and politics.

In 1892 he was selected as a delegate to the Republic Convention in Minneapolis, making him the first Black man south of the Mason-Dixon line to be so honored.

In 1908 he presented a petition with 10,000 signatures in order to run for Congress. The Republican party refused to have his name on the ballot, so he ran as an independent, losing to Jessie Overstreet.

He and his son purchased the “Indianapolis Freeman,” which he turned into a weekly newspaper for Blacks. Knox was active in its publication until he sold his interest in it in 1926.

Of all he accomplished in life, Betor said Knox was perhaps best known for the way he treated others.

“After he accumulated some wealth after the Civil War, he visited his old plantation owner and gave him financial aid,” she said.

George Knox died of a stroke in 1927, at which point one newspaper referred to him as “probably Indiana’s most prominent colored citizen.”

He was buried alongside his wife, Auralia, in Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis.

His descendants carried on his penchant for success. George Knox II was a member of the Tuskegee Airmen — American’s first group of black military airmen — and later joined the U.S. Air Force.

George Knox III grew up traveling with his military dad. He graduated from Tokyo American High School in 1961 and later worked at the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo. He earned a degree from Harvard University and retired as vice president of corporate affairs for Phillip Morris Co., according to thehistorymakers.com.

A free exhibit about Greenfield’s first Black businessman, George Knox, will be on display at the James Whitcomb Riley Museum through Sept. 6. The museum, at 250 W. Main St. in Greenfield, is open from 11 a.m.-4 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday.