GREENFIELD — As the rain beat down on the shelter house behind St. Michael Catholic Church on Saturday night, a few men — protected by tarps and fueled by coffee — stayed in the shelter hour after hour, transmitting radio signals to other amateur radio operators around the country.

This past weekend marked the annual Field Day Exercise, for which amateur radio operators — commonly known as ham operators — set up temporary stations in public locations to showcase the science and skill of amateur radio. The event has been taking place every year since 1933.

It’s like Christmas Day for many of the participants, who enjoy communicating and competing with other clubs across the country — accumulating points for connecting with others on the radio either verbally, through typed messages or in Morse code.

There’s a spirited competition among radio clubs to accumulate the most points by making calls, logging visitors, training the public on the radio and hosting elected officials to their event.

[sc:text-divider text-divider-title=”Story continues below gallery” ]

Click here to purchase photos from this galleryEach club keeps a log of their activity throughout the 24-hour event and submits their logs to the American Radio Relay League, which tallies the results and publishes them in its magazine.

The local club has never won, which isn’t uncommon for a club of just 25 to 30 members that operates at 100 watts or less. But the group always has a good time at the all-night event. Even when it pours down rain.

Ryan Ogle and Ed Tanaka of Indianapolis brought their 10-year-old sons by to try out some radio communications.

“I’m not a ham guy myself, but at the same time I certainly recognize that it plays an important role, especially if some kind of local disaster happens,” Tanaka said. “With the coronavirus stuff going on, it makes you realize that emergency communications like this are so important.”

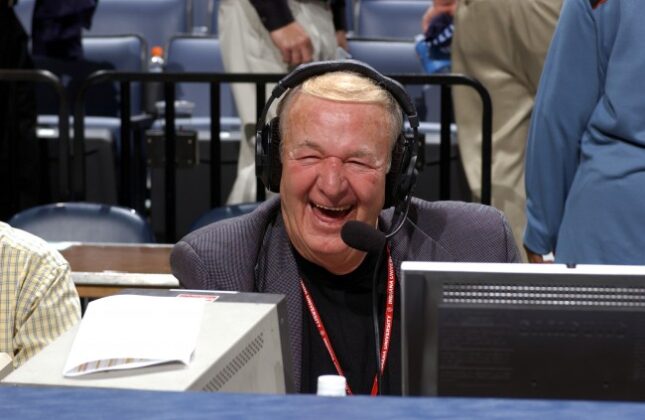

Jon Reeves, president of the Hancock County club, said that ham radio is more than just a hobby for many.

It’s also heavily relied upon for weather tracking and to help with communications during public emergencies, as it was in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

Reeves said Field Day is an exercise in emergency preparedness. “If you think of what happened in New Orleans with Katrina, they had three to four days before they had any communication sent out, but amateur radio operators went in there and set up and were getting messages out in pretty short order,” he recalled.

Amateur radio operators are licensed by the Federal Communications Commission. “We exist because the government recognizes our ability to help in disasters when normal communications are shut down,” Reeves said.

Amateur radio is self-contained, meaning operators can communicate from one antenna to another, without relying on larger networks.

“We can communicate with people from all over the world,” said Reeves, 67, of Greenfield, who got his amateur radio license when he was 16.

It was his fascination with ham radio that sparked his interest in becoming an electrical engineer, he said.

As a young boy, Reeves quickly got hooked on the ability to connect with fellow operators over the radio waves.

He first was introduced to ham radio at a Boy Scout fair, where another operator was demonstrating how he could communicate via voice or Morse code.

He quickly earned his amateur radio license and was connecting with people around the world, even out of this world.

He communicated via radio with an astronaut on the space shuttle Columbia as well as on the International Space Station, where an amateur radio is built in, Reeves said.

His favorite experience has relaying messages for soldiers to their loved ones back home.

One of the most fun parts of ham radio is sending out a signal to talk to anyone who might be listening.

“You never know what you’re going to get,” Reeves said. “You run into people from all walks of life, from doctors to plumbers to kings. King Hussein of Jordan was a ham operator,” he added.

As a college student in the early 1970s, Reeves would tie his radio into a phone line and transmit phone calls for people working at the South Pole.

“They didn’t have satellites, so when they were wintered there they did not have any contact with their families,” he said. “I’d make contact by radio, and they had people lined up who would give me a phone number and I’d call their family collect so they could talk.”

One time he connected with a U.S. Navy ship, and helped the sailors get in touch with their loved ones back home.

“They couldn’t tell me where they were, but there were sailors lined up in the hallway to call their wives,” said Reeves, who still gets choked up remembering the letter he got from one serviceman, thanking him for helping him call his wife.

“He said he hadn’t talked to her in almost a year. I still have the letter,” he said.

Ham radio enthusiasts have a great respect for amateur radio and the ways it’s helped connect people throughout the years, especially in states of emergency.

The annual Field Day event serves as a sort of stress test for amateur radio operators, Reeves said. “If you’re called out in an emergency, you are probably going to have to do this — set up a camp that’s self contained using generators,” he said.

Hancock County Emergency Management and other local officials have the names and numbers of local ham operators on hand in case of emergency.

“A lot of us are volunteers in emergency management too,” said Reeves, who serves the local emergency management agency as a technical consultant.

He’s also a member of the Radio Amateur Civil Emergency Service, known as R.A.C.E.S, which provides backup communications for local, county, state and federal governments in states of emergency.

If government communications go down, R.A.C.E.S. operators step in to help with communications, he said.

Greenfield Mayor Chuck Fewell, who stopped by the local Field Day event on Saturday, knows firsthand how essential ham operators can be in states of emergency.

He worked closely with ham operators during the blizzard of 1978, when he was an Indiana state trooper. “We worked with them to get dispatched out on snowmobiles,” he recalled.

If an emergency in Hancock County ever wipes out communication lines, ham operators will be the first ones called upon to help, the mayor said.

“We have all the modern techniques in the world, but when our communication towers go down, we can’t just go out and put up another one — but these guys can,” he said, gesturing to the ham operators around him Saturday.

“We can put a dispatcher with them, and using the radio, they can dispatch people to where they need to be,” Fewell said.

Reeves remembers helping out as a radio operator during the blizzard of 1978, and being dispatched to deliver blood to a hemophiliac. “I joined two guys in a Jeep and I got on the radio and was told to go to Wishard (Memorial Hospital, in Indianapolis) to get the blood,” he recalled.

Knowing you’re able to help out in an emergency is one of the biggest draws for ham radio operators, he said.

Fellow club member Bill Smith, 82, has had his amateur radio license for nearly 68 years.

“My dad had been a ham operator since before World War I,” recalled Smith, who lives in Fountaintown. “He made sure I kept learning Morse code so I could get my ham license,” he recalled.

Smith got his license when he was 16, and has been an avid operator ever since.

“Back in the Korean War we handled a lot of messages for servicemen,” Smith said. “They’d leave Korea and go to Japan for rest and recreation before going back to the battlefield, and they’d send messages through us to their loved ones back home.”

Even outside of war time, ham radio operators were called upon to transmit messages back when making long-distance phone calls — even just outside your own county — was cost-prohibitive.

“My father handled ham traffic almost every night for 30 years or more, sending messages and radiograms for people,” said Smith, one of the club members who stayed up around the clock at the 24-hour Field Day event.

Like many clubs with older members, Reeves said that HARC is interested in drawing in young members to keep the interest going for future generations.

Sometimes all it takes is one visit to Field Day to get a young person hooked, said Reeves.

He recalled a young boy who first visited the club’s Field Day when it was held at the Hancock County Fair over a decade ago.

The 8-year-old was so intrigued his mom let him spend all night at the HARC tent, learning about amateur radio. The boy soon got his radio license and joined the club when he was in high school.

“He got into the weather aspect of ham radio big time. He just graduated from Ball State as a meteorologist,” said Reeves, beaming with pride.

[sc:pullout-title pullout-title=”Learn more” ][sc:pullout-text-begin]

The Hancock Amateur Radio Club is a local club for amateur radio operators, otherwise known as hams.

There are over 761,300 licensed hams in the United States, as young as 5 and as old as 100, according to HARC. Anyone may become a licensed operator.

For over 100 years, ham radio has allowed people from all walks of life to experiment with electronics and communications techniques, as well as provide a free public service to their communities during a disaster through its independent communications network, without the need for a cell phone or the Internet.

Field Day demonstrates ham radio’s ability to work reliably under any conditions from almost any location. Over 35,000 people from thousands of locations participated in Field Day in 2019.

HARC was formed as a service to the local community to educate the youth and the public about amateur radio and electronics, and to serve as a communication resource during local disasters or emergencies. The club also provides a team of trained weather observers to provide visual sightings of severe weather conditions to the National Weather Service in Indianapolis.

To get involved with the Hancock Amateur Radio Club, contact club president Jon Reeves at [email protected]. To learn more about ham radio, visit the American Radio Relay League’s website at arrl.org/what-is-ham-radio.

[sc:pullout-text-end]